This article was first published in the Journal of Communication in Healthcare.

Inconsistent communication about COVID-19 from public officials has created mistrust and confusion about public health recommendations, which has contributed to increased mortality in the United States. National, state, and local leaders have offered conflicting narratives about the seriousness of the pandemic, the steps needed to contain it, and the safety of the vaccines that are beginning to be administered.

Effective crisis communication requires clear and consistent messaging – something our national and local response has lacked. Mayors and governors in the same states have often been pitted against each other, and nearly 200 state and local public health officials have been fired or have resigned after being subjected to harassment, threats, and political pressure. Much of this conflict has been over the choice of public health safety or the need to keep businesses and schools open. Framing this binary choice between public safety and the economy presents a false dichotomy, as containing the spread of COVID-19 is a prerequisite for a strong economy and a return to normal activities.

In 2021, with the arrival of promising vaccines and a new administration, officials at every level of government have an opportunity to learn from the past year and improve our national response. An important element of that effort is compelling and consistent messaging that can build widespread confidence in fact-based recommendations.

Two nationwide polls recently conducted by Frank Luntz and the de Beaumont Foundation reveal language that is most likely to motivate people to follow science-based public health recommendations and feel more confident about taking a COVID-19 vaccine. The first poll, conducted Nov. 21-22, 2020, covered a range of topics related to COVID-19 (800 registered voters, including 300 Black Americans, with a margin of error of 3%). The second poll, conducted Dec. 21-22, 2020, focused specifically on vaccines (1,400 registered voters, including 300 Black Americans and 300 Latinx Americans, with a margin of error of 3%). Respondents in both polls, representative of the nation’s demographics – including age, gender, race, and geography–were asked about the words, sentences, phrases, and attributes that would be most likely to motivate them to change their behavior in order to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Among the words that were tested are those cited in this article and in the figure below.

Positive and personal language

In the de Beaumont Foundation’s polls, respondents said the benefits of taking a COVID-19 vaccine would be more likely to motivate them than the consequences of not taking it, by a margin of 61% to 39%. One statement focusing on benefits that respondents identified as persuasive is: ‘We need to take measures to control the spread so we can return to a healthy economy and get back to normal day-to-day activities.’

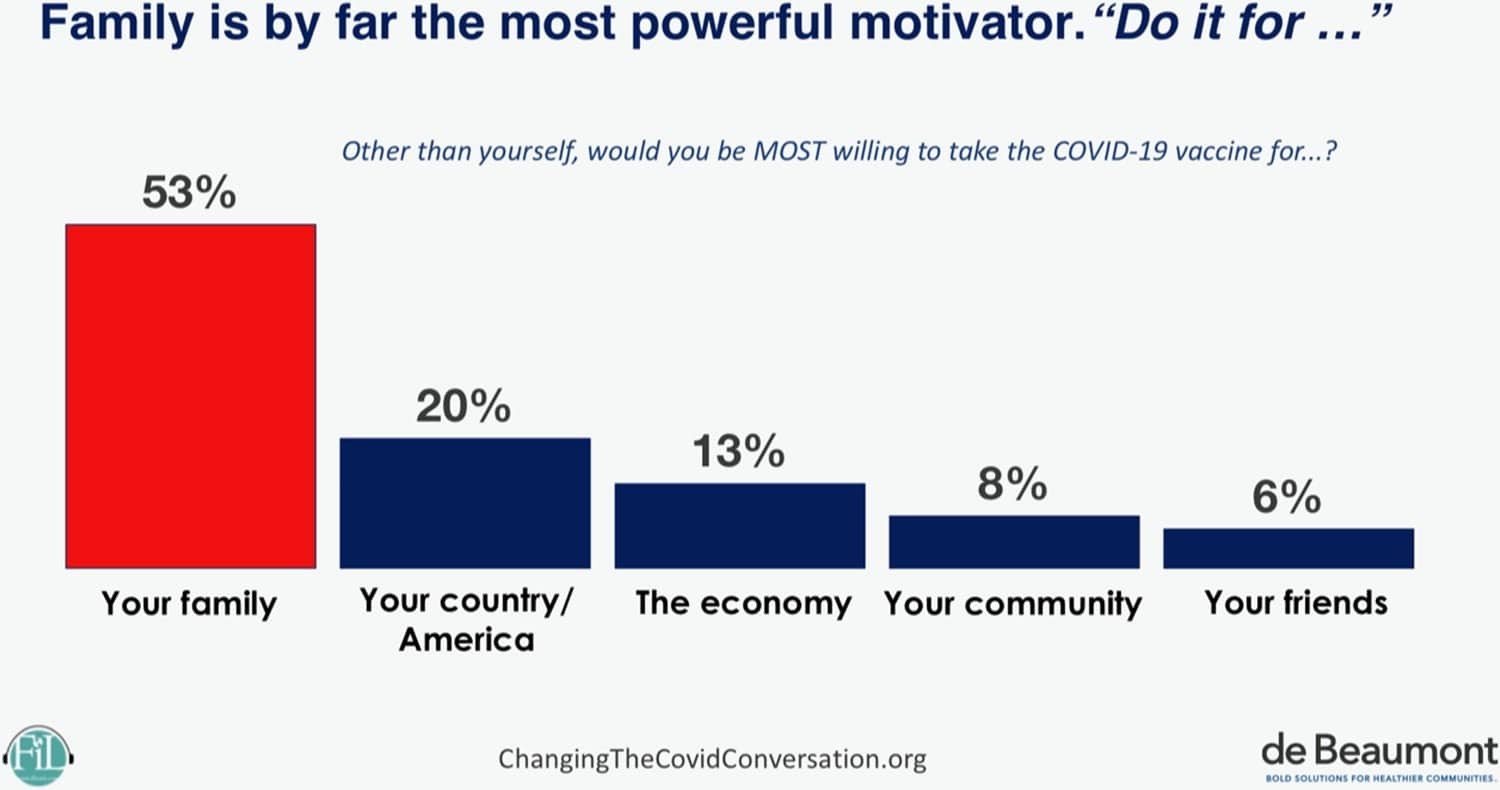

Respondents favored personal language—saying, for example, that they would be likely to trust ‘scientists, health and medical experts, and researchers’ more than ‘science, health, and medical companies.’ They care about the impact of the pandemic on their own family and friends more than ‘the nation’ or ‘the economy’ and consider it their ‘personal responsibility’ to do what they can to end the pandemic, not their ‘national duty.’ By a large margin, respondents said family is the most powerful motivator to get vaccinated, with 53% saying they would be most willing to take the vaccine for their family, compared with 20% who replied for ‘your country/America,’ 13% for ‘the economy,’ 8% for ‘your community,’ and 6% for ‘your friends.’

Overcoming fear and anxiety

In the de Beaumont Foundation polls, the two messages that were chosen most frequently among a list of 14 statements intended to increase confidence in vaccines were: ‘At 95% efficacy, the vaccine is extraordinarily effective at protecting you from the virus’ and ‘Vaccines will help bring the pandemic to an end.’ One-third of respondents (33%) said their biggest concern about the vaccine is either long-term side effects or short-term side effects, and that they would be most reassured by these statements:

- ‘The likelihood of experiencing a serious side effect is less than 0.5%.’

- ‘Mild side effects are normal signs that your body is building protection.’

- ‘Most side effects should go away in a few days.’

Building trust

Even among people who typically trust the government, the emphasis that federal leaders placed on developing a vaccine quickly–even calling the effort ‘Operation Warp Speed’–has created doubts about safety. Government officials and health professionals should be prepared to explain that the vaccines are safe despite the accelerated timeline. Among the messages respondents identified as most reassuring are:

- ‘A safety board approved every study, and the FDA carefully reviewed the data from every phase of every trial.’ (The repeated use of ‘every’ in this statement is deliberate.)

- Researchers were able to develop the vaccines so quickly because ‘data and findings were shared with researchers around the world on a scale that has never been done before, allowing for genuine international cooperation.’

- ‘The FDA will continue to collect data on each vaccine for two years after it is first administered to ensure that the long-term effects are safe.’

Gaining trust is particularly vital when communicating with vulnerable, marginalized, and underserved communities who regularly face systemic barriers and discrimination. The polls examined differences in words that likely to build trust about COVID-19 vaccines among Black and Latinx respondents. Overall, when respondents were asked to choose the words that would give them the most trust and confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine (from a list of 12), the two most popular words were ‘advanced’ and ‘groundbreaking.’ However, among Black respondents, the most preferred word was ‘innovative,’ and for Latinx respondents, ‘unprecedented’ was the first choice.

The following recommendations, based on the poll findings, can make communication about COVID-19 vaccines more likely to build confidence and acceptance:

- Use positive language. Emphasize the benefits of getting vaccinated and not just the consequences of not doing so.

- Humanize, personalize, and individualize language about the pandemic. People trust people more than institutions, and they care mostly about how the pandemic affects the health of friends and families.

- When promoting the importance of getting a COVID-19 vaccine, don’t moralize or lecture. Instead, listen to concerns, and answer questions directly and honestly. Emphasize that you want them to have factual information so they can make the right decision for themselves and their family.

- Tailor your messaging for your audience, because perspectives about the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines differ by age, gender, race, and geography.

The de Beaumont Foundation’s recent polls show that language choice matters. Effective health communication can save lives by improving confidence in public health guidance and COVID-19 vaccines. The success of government and health professionals in building confidence in the COVID-19 vaccine will depend largely on their ability to consistently use words that resonate with their intended audiences. By applying the words and phrases identified by the de Beaumont Foundation polls, health communicators can play an important role in improving vaccine uptake and ending the pandemic.

This article originally appeared in the Journal of Communication in Healthcare on April 7, 2021. See the final authenticated version here.