Public health literacy concerns how people comprehend and use information to act on public health decisions that affect the community. Research shows low rates of public health literacy among U.S. adults. (Photo credit: Rebecca Drobis)

Imagine you’ve just returned from a long walk on a hot day, and you go to pour yourself a glass of water. Just as you reach for the glass, your phone buzzes with a boil-water advisory for your neighborhood. But this time is different from previous alerts; there’s a poll connected to it: “Press 1 if you would like your local EPA clean water agency to address the problem and ensure your neighborhood’s water is safe to drink” or “Press 2 if you would like to be in charge of your own water supply from now on, either by purifying your own water or buying bottled water from the store.”

Most people would probably pick option 1. Not only does this solve the problem faster, but it provides a community-wide solution to a community-wide problem. No one person should be solely responsible for providing safe drinking water for themselves.

This scenario depicts the importance of public health literacy. Whereas health literacy concerns how people comprehend and use information to inform their personal health decisions, public health literacy goes further upstream, concerning how people comprehend and use information to act on public health decisions that affect the community. This may seem like a slight distinction, but it can lead to big differences in community outcomes. Understanding the role of public health in one’s everyday life requires understanding how community influences individual health; your health is not just the result of your own choices but also the many social determinants beyond your control. Conversely, it also requires recognizing that your health decisions can affect others, like choosing to get vaccinated or driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Despite overwhelming evidence that public health recommendations and efforts save lives and improve health, the public’s understanding of public health and public health literacy remains extremely low. In March and April 2024, the de Beaumont Foundation and CommunicateHealth conducted focus groups and in-depth interviews with 100 U.S. adults to assess public understanding of public health. Participants overwhelmingly showed low understanding of public health. For example, nearly all participants struggled to articulate what public health is, who public health professionals are, and what those professionals do. Many mistook public health for government programs such as Medicaid and Medicare. Further, many could not name public health professionals beyond those in health care or medicine.

What makes public health so difficult to comprehend? One barrier to literacy is that public health deals with health at the population level; this upstream perspective clashes with prevalent narratives framing health as an individual responsibility. On top of this, public health emphasizes prevention, but our systems are largely focused on treatment of existing medical issues. To complicate things further, public health is made up of complex layers, all of which require different types of literacies.

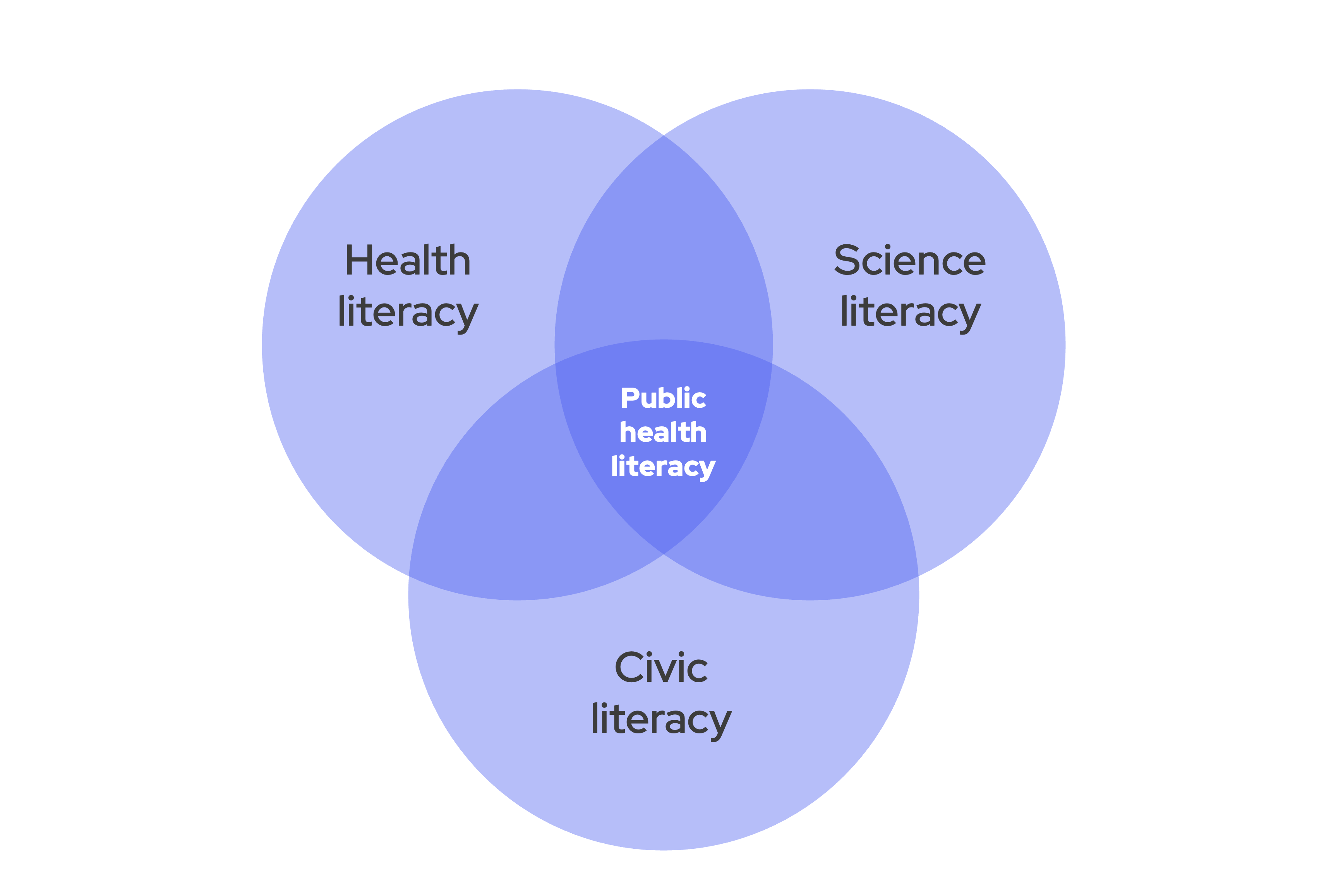

As the graphic below shows, public health literacy includes health, science, and civic literacy. People need a basic level of health literacy to make sense of public health guidance, or even access it in the first place. Science literacy is necessary to understand concepts like how germs spread or vaccines protect against viruses. Then there’s civic literacy: understanding how individual actions affect the community and vice versa, the concept of individual versus collective rights, and the role of policy in promoting health. These layers of literacies make it extremely difficult for people to grasp a complex topic like public health.

Public health literacy requires an understanding science literacy, health literacy, and civic literacy, making it particularly challenging to comprehend.

Further complicating public health literacy is the association of public health with COVID-19, which reinforces the conflation of public health and health care. In our research, the topic of COVID-19 elicited narrower discussions about public health related to vaccines, medical professionals, and medical laws and regulations. Most participants were unfamiliar with — and surprised by — activities of public health beyond COVID-19. They said examples like inspections, laws, and regulations were new to them and useful in explaining what public health entails.

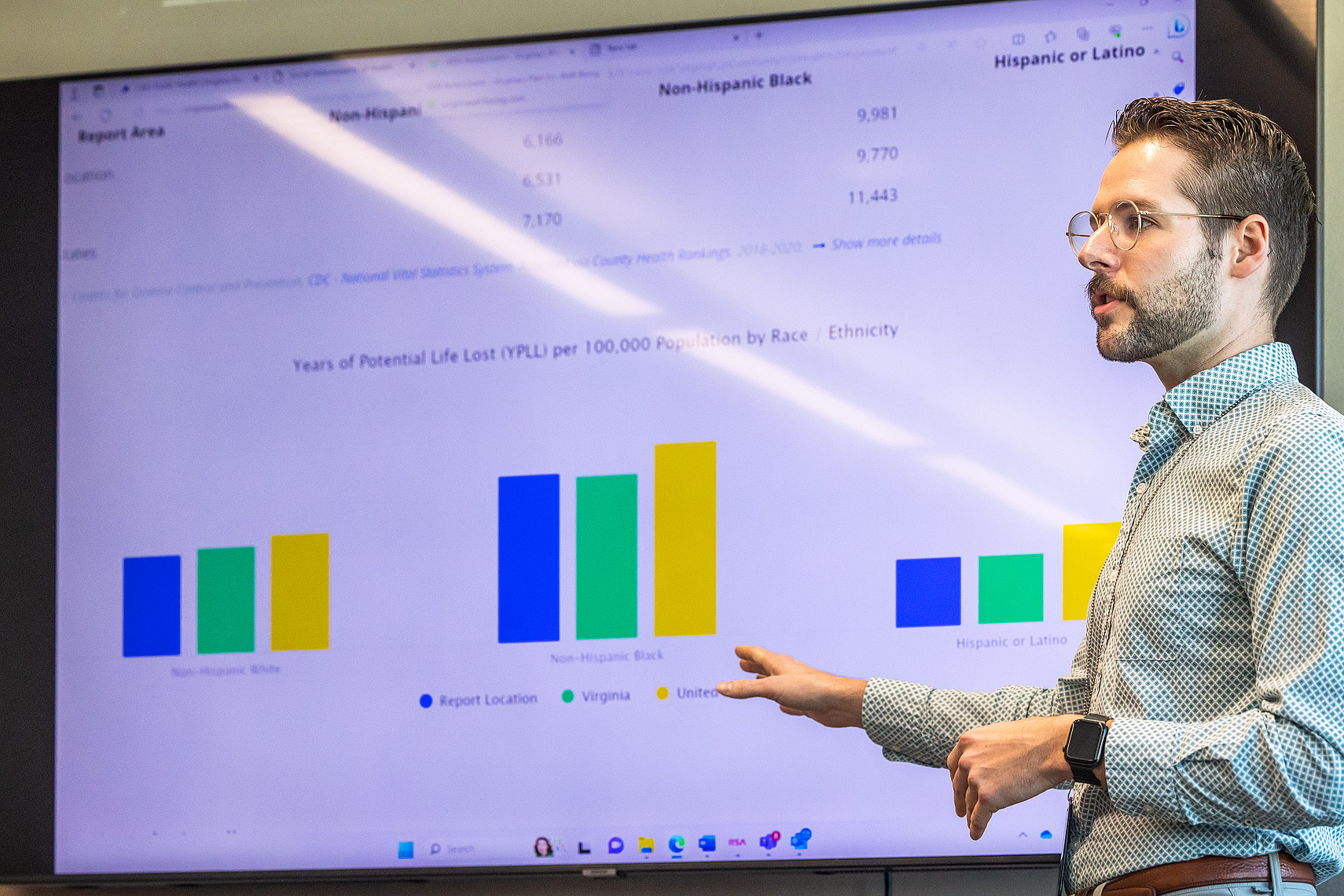

As the face of the field, public health professionals — including inspectors, health educators, scientists, social workers, and more — are well positioned to address this problem and build public health literacy in their communities. To do this important work, public health professionals need effective, research-based communication strategies that they can use in day-to-day interactions with community members. However, many public health institutions lack the resources to hire communications specialists or invest in substantial communications training.

To help fill this gap, de Beaumont and CommunicateHealth are developing a suite of plain-language messages and communication tools to help any public health professional communicate about public health activities, outcomes, and goals. The forthcoming suite of tools will be more than just tested messaging explaining what public health is and the value it brings to communities’ everyday lives. It will help users think about existing and new opportunities to communicate with the public about public health, and to leverage these opportunities strategically and effectively.

Public health recommendations and guidance can only do so much for communities. Public health literacy serves as the baseline for this information to be understood, adhered to, and valued. Increasing public health literacy is a critical step in ensuring that public health professionals can protect the health of our communities and individuals’ ability to make choices that protect their health and safety.