Until recently, efforts to improve the health of Americans have focused on expanding access to quality medical care. Yet there is a growing recognition that medical care alone cannot address what actually makes us sick. Increasing health care costs and worsening life expectancy are the results of a frayed social safety net, economic and housing instability, racism and other forms of discrimination, educational disparities, inadequate nutrition, and risks within the physical environment. These factors affect our health long before the health care system ever gets involved.

Hospitals and health care systems have started to address these social determinants of health through initiatives that buy food, offer temporary housing, or cover transportation costs for high-risk patients. The prevalence and initial success of these efforts are clear in headlines such as: “What Montefiore’s 300% ROI from Social Determinants Investments Means for the Future of Other Hospitals,” “Social Determinants of Health Gain Traction as UnitedHealthcare and Intermountain Build New Programs,” and “How Addressing Social Determinants of Health Cuts Healthcare Costs.” But when you take a closer look, these articles aren’t about improving the underlying social and economic conditions in communities to foster improved health for all – they’re about mediating patients’ individual social needs. If this is what addressing the social determinants of health has come to mean, not only has the definition changed, but it has changed in ways that may impede efforts to address those conditions that impact the overall health of our country.

In 2008, the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health defined those determinants as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age” and “the fundamental drivers of these conditions.” This term prioritizes a broad, community-wide focus on the underlying social and economic conditions in which people live, rather than the immediate needs of any one individual. While health care leaders have realized that programs to buy food, offer temporary housing, or cover ridesharing programs are less expensive than providing repeat health care services for their highest cost patients, such patient-centered assistance does not improve the underlying social and economic factors that affect the health of everyone in a community. While targeted, small-scale social interventions provide invaluable assistance for individual patients, we must also remain focused on the social determinants that perpetuate poor health at the community level.

A recent speech by Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Alex Azar highlighted the dichotomy between individual-level “social needs” and community-level “social determinants.” Secretary Azar emphasized that factors like housing and transportation have an important effect on Americans’ health. He asked rhetorically, “How can someone manage diabetes if they are constantly worrying about how they’re going to afford their meals each week? How can a mother with an asthmatic son really improve his health if it’s their living environment that’s driving his condition?” And he appropriately noted that we “can’t simply write a prescription for healthy meals, a new home, or clean air.”

In his discussion of how to address health-related community conditions, Secretary Azar, like a growing number in health care, focused on the social needs of individual patients. In his speech, he recounted the success of the Accountable Health Communities model, noting that “participating providers screen high utilizers of healthcare services for food insecurity, domestic violence risk, and transportation, housing, and utility needs. If needed, patients are set up with navigators, who can help determine what resources are available in the community to meet the patient’s needs.” He even went so far as to suggest that Medicaid may allow hospitals to pay for housing, healthy food, and other services. But in order to improve our nation’s health, we must look beyond “superutilizers,” Medicaid recipients, and those who are already sick. Secretary Azar appropriately noted that health care navigators “can help determine what resources are available in [a] community.” However, while growing in popularity, health care navigators and similar enhancements to health care can’t actually change the availability of resources in the community. They can’t raise the minimum wage, increase the availability of paid sick leave, or improve the quality of our educational system. These are the systemic changes that are necessary to truly address the root causes of poor health.

Efforts To Address Social Needs Are Necessary, But Not Sufficient

Even if they don’t address broader social conditions within patients’ communities, health providers’ efforts to meet individuals’ non-medical needs are praiseworthy and potentially life-saving. In Chicago, Advocate Health Care saved nearly $5 million by screening for malnutrition risk factors and establishing an enhanced nutrition care program. In Boston, a six-months-or-longer, home-delivered meals benefit for dual Medicare-Medicaid eligible patients was associated with significant reductions in emergency room visits and overall health care cost savings. An initiative to link WellCare Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plan members to social service organizations resulted in an annual savings of $2,400 per person. In Hennepin County, Minnesota, millions of dollars were saved by offering unconventional services to patients with complex health, housing, and social service needs. The University of Illinois at Chicago reduced costs by 18 percent by identifying homeless patients who could benefit from housing support. These are just a few of the studies and reports documenting the health care system’s efforts to go beyond its own walls to improve health outcomes, decrease consumption of medical services, and reduce costs.

While individual-level interventions are beneficial, characterizing them as efforts to address social determinants of health conveys a false sense of progress. These strategies mitigate the acute social and economic challenges of individual patients, but they do so without implementing long-term fixes. They are often limited to a small segment of the population – those who are in the worst health and have the greatest health care costs. Meanwhile, those patients who do not rank among the “sickest and most expensive” are ignored.

We Need Policy Changes That Target Social Determinants Of Health

Policy makers have the power to address the social and economic conditions that affect community health. For example, in Kansas City, Missouri, voters recently approved a ballot initiative empowering health inspectors to respond to tenant complaints about a broad range of housing conditions, funded by an annual fee of $20 per unit for landlords. Earlier this year, the City Council of Alexandria, Virginia voted to raise the city’s meal tax to fund affordable housing. These communities and others like them have embraced the need for policy intervention to improve the social determinants of health for their citizens.

National initiatives offer states and local communities a roadmap for identifying and implementing gold-standard strategies to improve public health. In an initiative known as Health Impact in 5 Years (or HI-5), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a list of 14 evidence-based policies to improve population health. CityHealth, an initiative of the de Beaumont Foundation and Kaiser Permanente, provides city leaders with a package of nine policy solutions that can help millions of people live longer and better lives.

Hospitals and health systems may be stepping up by referring a patient with mold in his or her apartment to a tenant’s right advocate, feeding a patient who needs food, or providing an on-site exercise program. But these interventions do not address the mold in that patient’s next-door neighbor’s apartment, community access to healthy food, or the availability of low-cost exercise options. These community-level changes can only be made through policy action. While they work to address their patients’ immediate needs, hospitals and health systems would do well to recognize and support community-level policy actions.

Not An Either/Or – Social Needs And Social Determinants Must Both Be Addressed

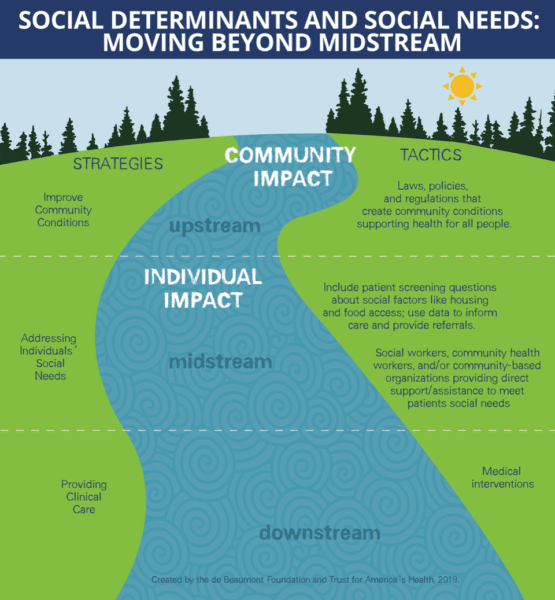

This isn’t about picking one approach over another – we need social and economic interventions at both the community and individual levels. We often discuss health using the metaphor of a stream, with upstream factors bringing downstream effects. Social needs interventions create a middle stream (Exhibit 1). They are further upstream than medical interventions, but not yet far enough. Social needs are the downstream manifestations of the impact of the social determinants of health on the community. Improvements in our nation’s health can be achieved only when we have the commitment to move even further upstream to change the community conditions that make people sick. The demand for social needs interventions won’t stop until the true root causes are addressed. This should ring especially true as the movement to Accountable Health Communities and value-based care gains momentum. Any success these new payment structures enjoy will be short-lived if the underlying social conditions in the communities where they work remain unchanged. While the allure of short-term economic gains from mediating patients’ social needs nearly ensures media and stakeholder attention, the incentives to advance policy, legislation, and regulation to improve health more broadly are often less clear. Redefining the meaning of “social determinants” to be mostly or only about the immediate social needs of expensive patients makes it harder to focus on the systemic changes necessary to address root causes of poor health.

Words Matter: For Understanding. For Clarity. For Change.

In 2003, David Kindig and Greg Stoddart offered a comprehensive definition of population health. Twelve years later, Kindig expressed concern that the use of the term had grown too broad, writing that it’s “growing use, most notable in the Triple Aim and in clinical settings, has resulted in a conflicting understanding of the term today.” Is the term “social determinants” heading for a similar fate? If we, even inadvertently, imply that the social determinants of health can be solved by offering Uber rides to individual patients or by deploying community health navigators, it will be challenging, if not impossible, for public health advocates to make the case for proven policies like alcohol sales control, complete streets, and healthy food procurement.

Words matter. Common definitions ensure that we understand each other. When health care leaders and public health officials use “social determinants of health” to mean different things, it becomes more difficult for us to engage meaningfully with community partners, who will struggle to differentiate between these complementary but different approaches. This may seem like semantics, but when we use this term too broadly, we risk losing the specificity needed when calling on partners to make far-reaching social change, and we weaken our ability to implement the community-level efforts necessary to improve community health. And, ultimately, that doesn’t help any of us get healthier.

Click link to download the infographic “Social Determinants and Social Needs: Moving Beyond Midstream.”

Published by Project HOPE/Health Affairs as Brian Castrucci and John Auerbach. “Meeting Individual Social Needs Falls Short Of Addressing Social Determinants Of Health.” Health Affairs Blog (Millwood), January 16, 2019. The published post is archived and available online at https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190115.234942/full/.